Thursday, 30 July 2015

FORM OF FEDERAL (MALAYA) INTERFERENCE IN STATE (SABAH) AFFAIRS

Although much publicity was given to the status that Sabah would enjoy in the proposed Federation and the range of safeguards that would be granted to the State, the interference of the Federal government in State affairs actually commenced within months of the birth of the Malaysia nation. The saga began with the tussle for control of the State government between Tun Fuad and Tun Mustapha, the outcome of which was dictated by Kuala Lumpur. Paul Raffaele in his book Harris Salleh of Sabah gives an accurate assessment of the event:

“… Although the early leaders of Sabah had hoped that Malaysia would be a true Federation and not a unitary state, post-independence history has shown that when the interests of Sabah and Kuala Lumpur clash, the Federal government will step in unhesistantly and bring its younger partner to heel. Tunku Abdul Rahman saw the Kadazan Chief Minister as less than totally committed to Malaysia, unlike his friend Mustapha who saw the new Federation as giving power support to his claim of Malay and Muslim political primacy in Sabah” (Raffaele, 1986, p.30)

The details of the events surrounding the Mustapha-Fuad crisis are well documented in history books. Suffice it to say that the difference between the two leaders lie in the fact that while Tun Fuad Stephens was jealously guarding the State’s rights in pursuance of the original safeguards and promises, Tun Mustapha was more interested in strengthening Islam and developing Malay dominance in Sabah, regardless of its effects on state affairs. Numerous clashes between the two leaders can be traced to these fundamental differences in outlook and orientation. For instance, Tun Mustapha refused to approve the appointment of John Dusing as State Secretary, in contravention of the behaviour of a constitutional Head of State. However, all this was done with the help of the Federal Secretary in the person of Mr. Yeap Kee Aik whose major role was to strengthen Kuala Lumpur’s hold on the frontier State, by ensuring that “any party favouring Malaysia should prosper while being unfavourably disposed to any party that seem to have doubts about the Federation” (Raffaele, 1986,pp. 142-144)

This has led some scholars to describe the 20 Points safeguard as follows:

“The intent of the safeguards was to give State leaders the illusion of having greater control than they in fact possessed, but illusions which they were to take very seriously.” (Ross-Larson, 1980).

The Mustapha-Stephens crisis can be aptly described as follows:

“The two (referring to Tun Mustapha and Tun Fuad Stephens) were unwitting actors in a drama written by the Federal government, and both felt compelled to play out their roles, however reluctantly.” (Ross-Larson, 1980)

The hands of the Federal government in shaping the political development and accelerating the erosion of State’s constitutional safeguards, can be clearly seen in the selection, encouragement and support for a state leader who reflected the Federal cause, who in the immediate years after Independence was none other than Tun Mustapha. In order to further ensure that the new State government would not be too independent-minded and thereby jeopardise federal’s interests in the State, Syed Kechik, a strong UMNO supporter and the political secretary to the Minister of Information, was assigned to assist Tun Mustapha. Syed Kechik’s contributions included the introduction of various constitutional amendments and new laws to shift the power from the State to the Federal government. It is believed that he was also instrumental in the resignation of top civil servants who were thought to be pro-state and their replacement by Federal sympathizers.

Whenever the question of who should bear the responsibilities for the erosion of the constitutional safeguards is raised, the standard answer is that it was the doings of the Sabah leaders themselves. However, history has shown that during the USNO’s rule the erosion of constitutional safeguards on education, language and religion can be directly traced to machinations of Kuala Lumpur’s appointees including Syed Kechik, the then Attorney General of Sabah and other Federal officers who were unsympathetic and unmindful of their far-reaching consequences on the State.

For the sake of harmonious and enduring Federal-State relationship in the future, the Federal government has as much obligation as the State government in upholding the constitutional safeguards.

In instances where erosion of constitutional safeguards has occurred either unwittingly or erroneously, the parties involved should take steps to restore such rights, otherwise inaction would be interpreted as a deliberate scheme to weaken the power of the other party.

In the final years before the rise of BERJAYA in 1976, Tun Mustapha began to lose favour with the Federal government. This was primarily because of the misuse of his draconian powers, bestowed on him originally by the Federal government, which eventually made him a political liability to Kuala Lumpur. His plan to break away from the Federation by proposing the formation of Borneosia and establish his sultanate was also an important factor which contributed to his fall from the grace of the Federal government. But by then, Tun Mustapha had paved the way for the erosion of the safeguards on Education, Language and Religion. Throughout his regime, the Federal government essentially abandoned the people of Sabah to his abuse of their democratic rights and his squandering of the State’s natural resources. When political intervention would have been justified, and indeed was most needed, Kuala Lumpur opted to assume a spectator’s role to the great disappointment of the people of Sabah.

The emergence of BERJAYA and the success it had in deposing the regime of Tun Mustapha occurred with the support of the Tun Razak government. In its early stage of development, the party sought earnestly to reverse the excesses of Tun Mustapha. However, when its leaders were assured of deriving support from the Federal government, it committed the same excesses as its predecessor. As with Tun Mustapha’s Administration, the Harris’ Administration became increasingly more autocratic and intolerant to well-intended public criticisms. It distanced itself from the Rakyat by pursuing policy objectives contrary to the wishes and aspirations of the people. It had even gone to the extent of changing the district status of Tambunan just to punish the voters who defied his order to support him. His abuse of power included the liberal use of Federal and State machineries in the 1985 general elections campaigns.

In the ensuing years Datuk Harris’ Government committed other political excesses similar to those of his predecessor. The problem of illegal entrants obtaining blue IC became increasingly more acute without his government doing something about the problem. Datuk Harris’ Government promoted massive conversion to Islam among indigenous Sabahans by granting favours to prospective converts. His government’s desire to keep the Federal happy culminated in the signing away of Labuan, free of charge, without the consent of the people of Sabah, although on the surface the federalisation of Labuan appeared to have been properly executed by subtly forcing an enactment through the State assembly. The act was also a breach to the Twenty Points safeguards.

When the PBS came into power, the Federal government could not accept the defeat of the party that had been so accommodating to Kuala Lumpur’s drive towards a unitary state. Amidst the events that followed the power grab at the Istana until the next general State elections in 1986, when the people of Sabah were forced to give their verdict on the legality of the government of the day, traces of Kuala Lumpur’s involvement were obvious. The fact that those involved in the power grab were let loose caused many Malaysians to take a dim view of the rule of Law as there was a clear case of miscarriage of justice. Between April 21, 1985 and May 5, 1986, two State general elections were held in close succession because of the reluctance of certain Federal leaders in endorsing the results of the 1985 general elections which saw the defeat of the Federal-anointed party. Prime Minister Datuk Seri Dr. Mahathir Mohammed when interviewed about the unsettled political climate in Sabah, was widely reported to have said that he himself was not sure as to which government, the ruling PBS Government or the contending USNO-BERJAYA coalition Government, would the Court uphold as the duly elected government of the people of Sabah.

It is amazing that the vanquished parties even had the audacity to hail the victor to court and demanded that they be installed to replace the rightfully elected government by claiming to represent the wishes of the majority of the people. While the people of Sabah were fearing for their lives, no decisive action was taken by Federal Government until the tense situation escalated into outbreak of lawlessness causing losses of property and lives. When those responsible were finally brought before the courts the charges handed out were viewed by Sabahans as a mockery vis-à-vis the extent of damages, human tragedy and economic losses caused by the rioters. Indeed, there were broad hints that some quarters were using the March 1986 riots to justify the imposition of Emergency rule in sabah by the Federal government, as a way to replace the democratically elected government.

Finally, many Sabahans consider the proposed entry of the UMNO into Sabah as not entirely unrelated to the issue of political interference. While the move has been cast in the name of championing Muslim cause and so-called bumiputera rights, the timing of the exercise and the past records of Kuala Lumpur’s interference in State affairs leave many nationalistic Malaysians of local origin unconvinced that the move will lead to any enhancement of Federal-State relations. Indeed Sabahans take the view that the whole exercise will be detrimental to national unity because the promotion of communal politics in Sabah will bring about racial and religious polarisation and split the already well-integrated people of Sabah. In the long term, communal politics go against the spirit of multiracialism which the Sabah leaders have so tirelessly championed. The proposed move of UMNO into Sabah also indicates the lack of understanding by the Federal leadership on the socio-cultural and psychological makeup of the people of Sabah. Unlike the people in Peninsular Malaysia, where people can be conveniently classified into Malays, Chinese and Indians, in Sabah, the racial and religious differences are unimportant as they are already well integrated.

It is to be noted that Malaysians in Sabah as represented by their leaders and political parties, have proven their ability to govern Sabah themselves for the past 23 years since the formation of Malaysia, without the presence of any Peninsular party or parties.

There is no need for UMNO, PAS, DAP or any other Peninsular parties to come to Sabah. It would be redundant. The important thing is for Kuala Lumpur to be able to foster and work with the ruling group in Sabah and Sarawak.

Thursday, July 30, 2015

Agreement of Malaysia

,

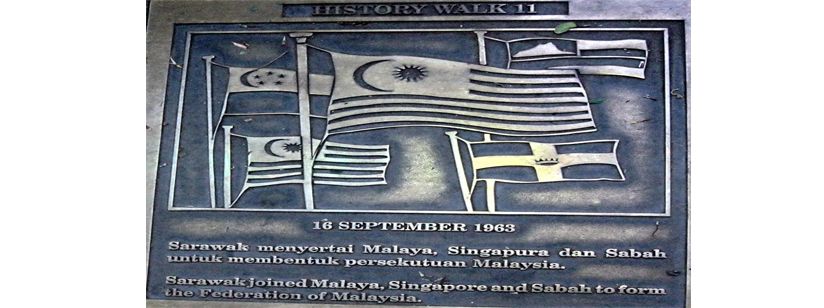

Federation of Malaysia 16 September 1963

,

Sabah

,

Sarawak

No comments

THE MALAYSIA PROJECT AND THE STATUS OF SABAH IN THE FEDERATION

On 27 May, 1961, Y.T.M Tunku Abdul Rahman Putra Al-Haj, the Prime Minister, Federation of Malaya, at a press luncheon in Singapore made the proposal that a Federation of Malaysia should be created, comprising the eleven States of Malaya, Singapore, the three Borneo territories of Sarawak, North Borneo and Brunei. The regularly quoted words of the Tunku were as follows:

“… Sooner or later she (Malaya) should have an understanding with the peoples of Singapore, North Borneo, Brunei and Sarawak… these territories can be brought closer together in a political and economic cooperation” (speech made by Tunku Abdul Rahman on 27 May, 1961 to the Foreign Correspondents of Southeast Asia in Singapore).

Later, on 16 October, 1961, the Tunku explained to the Malayan Parliament the motivation and framework for the formation of the Federation of Malaysia as follows.

“… When considering the concept of Malaysia it is necessary to keep in mind that the independent Federation of Malaya has to take note of three separate elements and the special interests of each. These three elements are the State of Singapore, which is almost completely self-governing, the three Borneo territories which are still colonies, and the United Kingdom which has special obligations or duties in relation to the people of these areas.”

“… I will turn now to the problem of the Borneo territories in relation to the concept of Malaysia. These territories do not present the same complexity in the implementation of the concept as Singapore does. In a broad sense, it could be stated that the question is much simpler there, in fact so much simpler that they present a special difficulty of their own. The three Borneo territories have two political factors in common. First… vestiges for British colonialism. Second… their constitutional development has been very slow” (speech by Tunku Abdul Rahman, Prime Minister, the Federation of Malaya, in the Federal Parliament on 16 October, 1961).

Amidst all the rhetoric which accompanied the campaign for an enlarged Federation, the plan to include the States of North Borneo, Sarawak and Brunei was, however, somewhat coincidental, for what the Tunku really wanted was Singapore. Nevertheless, the Tunku had one genuine aim for the Borneo territories – independence from the British colonialism. As he put it then:

“… it is our duty to help bring about an end to any form of colonialism. The very concept of Malaysia Plan is an effort to end colonialism in this region of the world, in a peaceful and constructive manner. We in Malaya won our independence by peaceful means and we are sure that the people of the Borneo territories would like to end their colonial status and obtain independence in the same way."

“… the important aspect of the Malaysia ideal as I see it, is that it will enable the Borneo territories to transform their present colonial status to self-government for themselves and absolute independence in Malaysia simultaneously.”

On the British Government’s side, it was not an issue to grant independence to the Borneo States (North Borneo, Sarawak and Brunei), since the British Government had decided to allow these territories to attain their own independence ultimately. The question was one of timing and the form it should take. As one document puts it:

“… The declared aim of the British Government is to grant independence to all its colonial territories as soon as they are ready for it. Hitherto this has been thought of simply as independence fo North Borneo standing by itself or, more recently, in association with Sarawak.”

“… It is the view of the British Government that provided satisfactory terms of merger can be worked out, the plan for Malaysia offers the best chance of fulfilling its responsibility to guide the Borneo territories to self-government in conditions that will secure them against dangers from any quarters.”

“… Malaysia offers for them all the prospect of sharing in the destiny of what the British Government believes will be a great, prosperous and stable Independent State within the Commonwealth” (Extract from “North Borneo and Malaysia” published by Authority of the Government of North Borneo, Jesselton, February 1962)

Even at the point in time, there was considerable concern that the notion of ‘independence through Malaysia’ might not be the sort of independence that the Borneo States were looking for. There were those who were concerned about neo-colonialism. On this issue the Tunku had the following to say:

“… One reaction in the Borneo territories was that the Malaysia concept was an attempt to colonise the Borneo territories. The answer to this was, as I said before, it is legally impossible for the Federation to colonise because we desire that they should join us in the Federation in equal partnership, enjoying the same status between one another, so there is no fear that Malaysia will mean that there will be an imposition of Islam on Borneo… everybody is free to practise whatever religion.” (Extract of speech by Tunku Abdul Rahman, Prime Minister of the Federation of Malaya, in the Federal Parliament on 16 October 1961)

In addition, the colonial government of North Borneo had cautioned that:

“… It is necessary, therefore, for the people of North Borneo to consider what powers they are prepared to concede in order to bring Malaysia into being. It is understood that there should be widespread apprehension lest, in practice, Malaysia would mean that the people of North Borneo would have far less control over their own affairs than they exercise already, and that North Borneo would be relegated to the position of a relatively powerless province of a strong Federal Government situated 1,000 miles away” (Extract from ‘North Borneo and Malaysia’)

For this reason, in the same speech the Tunku raised the issue of constitutional safeguards:

“… Moreover in our future constitutional arrangement the Borneo people can have a big say in matters on which they feel very strongly, matters such as immigration, customs, Borneonisation, and control of their State franchise rights.” (Speech by Tunku Abdul Rahman in the Federal Parliament on 16 October 1961)

The need for consultation and non-interference in the normal affairs of the Borneo State was highlighted by the Tunku.

“… One very strong feeling was that they must be consulted on the future of their people and the future of the country. I have said on more than one occasion that Malaya can only accept Borneo people from an expression of their own free will to join us.”

Other observers noted that:

“… In conversation with members of the North Borneo delegation to the Malaysia Solidarity Consultative Committee he (the Tunku) has made it abundantly clear that he has no wish to interfere in the internal affairs of North Borneo and is willing to consider sympathetically any proposal for the management by the people of this country of their own internal affairs.” (IGC Report)

Even the Colonial Government of North Borneo cautioned strongly that:

“… It would, indeed, be against the long-term interest of the Malayan Government to insist on excessive control against the wishes of the people of the Borneo territories, which would over the course of the years build up resentment and discontent leading to a repetition within Malaysia of the internal stresses and strains which, in recent years, have become apparent within the framework of Indonesia, and, more recently still, have culminated in the secession of Syria from the United Arab Republic." (‘North Borneo and Malaysia’)

Arising from the various public statements on the need for safeguards and conditions, formal steps were undertaken to identify these safeguards and to present them for discussion by political leaders and officials of all the parties involves. A strong starting point for these discussions was the submission of a Memorandum containing the ‘Twenty Points’ on 29th August, 1962 by the leaders of five newly formed political parties (The United Kadazan Organisation, The United Sabah National Organisation, The United Party, The Democratic Party and The National Pasok Momogun organisation). The Memorandum was a joint declaration setting out the basis on which Malaysia would be acceptable in North Borneo and embodying minimal safeguards in the form of Twenty Points which the parties considered necessary for North Borneo in its entry into Malaysia. The signatories to the 20 Points Memorandum were as follows:

The principles of the 20 Points were accepted in total. The implementation of the Twenty Points was discussed at length by the IGC and most of them were subsequently taken up and incorporated in the Malaysia Agreement.

Discussion of the details of the various safeguards and conditions is the subject of the next section of this Memo. Suffice it to emphasize here that security consideration and economic development were important motivations for support for the proposed Federation, which was identified with independence in the mind of the People. Certainly, there existed as expectation that the new Federation will be conducive to harmony among ethnic groups and economic advancement in the rural areas.

The process of bringing the Malaysia Project to fruition was of course a lengthy and arduous task. It involved, among others, the Cobbold Commission of Inquiry, IGC and UN Malaysia Mission. While these bodies all came to the conclusion that the leaders and people of Sabah generally “expressed strong support for the establishment of the Federation of Malaysia” it is crucial to note that their views were by no means unanimous. The main finding of the Commission of Inquiry deserves to be mentioned here:

“… In accessing the opinion of the peoples of North Borneo and Sarawak we have only been able to arrive at an approximation. We do not wish to make any guarantee that it may not change in one direction or the other in the future.”

“… About one third of the population in each territory strongly favours early realisation of Malaysia without too much concern about terms and conditions. Another third, many of them favourable to the Malaysia Project, asked with varying degrees of emphasis, for conditions and safeguards varying in nature and extent: the warmth of support among this category would be markedly influenced by a firm expression of opinion by Governments that the detailed arrangement eventually agreed upon are in the best interests of the territories. The remaining third is divided between those who insist on independence before Malaysia is considered and those who would strongly prefer to see British rule continue for some years to come…"

"There will remain a hard core, vocal and politically active, which will oppose Malaysia on any terms unless it is preceded by independence and self-government; the hard core might amount to near 20 per cent of the population of Sarawak and somewhat less in North Borneo.” (Extract of the Commission of Inquiry, North Borneo and Sarawak, 1962 – HMSO SMND, 1974).

The reservation exhibited by the people of Sabah (about two-thirds) as regards the proposed Federation served to emphasise the importance they attached to the provision of specific safeguards and conditions because of the uncertainty of their future in the enlarged Federation. The issue of safeguards and their fulfilment by the Federal government was very basic to their decision to form the Federation. Any violation of the safeguards would constitute a violation of the conditions upon which the State agreed to be a party to the formation of the Federation of Malaysia.

In retrospect, the vision of the Tunku, the aspirations of the Sabahan leaders and the consent of the Colonial Government as regards the formation of the Federation of Malaysia all converged on the important conclusion that:

(a) Sabah would participate in the formation of the Federation in equal partnership with Malaya, Singapore and Sarawak;

(b) The Federal government would not interfere in the internal affairs of Sabah, which would also be consulted on the future of her people and the future of Malaysia;

(c) There would be autonomy in specific areas of government;

(d) The new Federation promised an independence state and an improved economic well-being to the people of Sabah.