Monday, 6 July 2015

Professor: Sabah demands reasonable

KOTA KINABALU: The talks about secession by certain non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and politicians should not be viewed as a security threat by the government, said Universiti Malaysia Sabah (UMS) Head of International Relations programme, Professor Dr Kamarulzaman Askandar.

He opined that the authorities should instead put more efforts into finding the root cause of the problem from which the ideas to secede arose.

“When trying to diagnose an illness, for instance, the key is to inspect internally rather than to simply rely on surface analysis. Hence, rather than consuming efforts on searching for and apprehending individuals promoting secession, more efforts should instead be put into understanding the core on which such demand was built.

“These people (involved in secession issue) based their demand for secession on points such as where Sabah and Sarawak stood at the time of Malaysia’s formation, division of power, distribution of development priorities, and so on.

“For me, this is not merely a security issue but rather, we need to work on finding what it is that caused for such demand to arise and why,” he opined.

Kamarulzaman was speaking on a topic entitled, “Conflicts, Peace and Nation Building”. He was one of the four speakers who presented papers related to Sabah in the context of security, during the Nation Building Seminar at the YTL Auditorium, UMS, here yesterday.

Answering a question from the floor during the question and answer session after his talk yesterday, on whether the demands made by Sabah were reasonable, Kamarulzaman replied in the affirmative.

“In the case where an inch is given and a yard is taken, then there is a need to determine whether or not the demands are reasonable.

“When there are things formally promised through an agreement, like the 20-Point agreement in Sabah’s case, for example, it could mean that demands were made because there was something lacking in the process of implementing those promises.

“And while it’s not my place to say whether or not the demands made by Sabah are reasonable, I think it’s reasonable to expect consistent supply of electricity for instance, or for roads to be in good condition, for remote villages to get the basic necessities, or for all children to get quality education,” said Kamarulzaman.

The professor believed that in finding the solutions for peace among all the races in Malaysia, balance is the answer, whereby when there is imbalance in dividing priorities and a certain race gets the bigger slice of the cake, dissatisfaction is bound to surface.

“Each ethnic group has its own identity and while we talk about finding balance and peace, questions such as ‘Why are the Malays or the Muslims more dominant? Why are other ethnics or religion not given as much ‘airtime’ as the Malays and Muslims?’ arise.

“And in the context where a certain group of people receives more benefits and more opportunities than the rest, there will come a time when the oppressed – those who are not getting what they want and need, or simply not getting what they are promised – will revolt or at least voice their cry for their rights and values to be upheld,” said Kamarulzaman.

Concluding his talk, he said while Malaysia was way past its infancy, the concept of nation in this country was still vague.

“We are still working on finding the meaning of a Malaysian nation and still looking for the proper balance. If we cannot find the answer in my lifetime, I apologise on behalf of my generation and it will be up to the future generation to keep on it.

“But never be afraid of variety because that is where our strength instead of weakness lies, so long as we find the proper balance.”

The last of the White Rajahs: The extraordinary story of the Victorian adventurer who subjugated a vast swathe of Borneo

|

| Jungle kingdom: Borneo's Dayak warriors had a fierce reputation |

Few things frightened the Dayak warriors of Borneo, who were infamous for the gruesome custom of head-hunting. But on a December day in 1912, a series of thunderous booms reverberated across the island’s misty swamps and sent them racing towards the shelter of their huts.

Many feared they were about to endure the wrath of the gods or at least a severe storm. But it was in fact a man-made cacophony, a 21-gun salute to announce the birth of a male heir to the throne of Sarawak, the small jungle kingdom on Borneo’s western coast.

The baby whose arrival was so celebrated that day was not, as might have been expected, one of the Dayaks, Malays or Chinese who made up Sarawak’s population of half a million.

Indeed, Anthony Brooke could hardly have been more British. Born thousands of miles away in England, he would later be educated at Eton and Oxford. Yet as far as the people of Sarawak were concerned, he was royalty.

Since 1841, his father’s family had taken it upon themselves to rule this remote region as their private empire. The White Rajahs, as they became known, had the power of life and death over their subjects, not to mention their own constabulary, flag and postage stamps.

Anthony, too, would go on to govern Sarawak. In fact, this bizarre and extraordinary dynasty — known as much for its eccentricity as for its benevolent rule — only came to an end this month when he died at the age of 98.

The family had come to power thanks to Anthony’s great-great-uncle James Brooke — a man so swashbucklingly adventurous that Errol Flynn once proposed to play him in a film about his life.

The family had come to power thanks to Anthony’s great-great-uncle James Brooke — a man so swashbucklingly adventurous that Errol Flynn once proposed to play him in a film about his life.

Born in Benares in 1803, he was the son of an English judge who worked for the East India Company.

As a young man he joined the Bengal Army, waging war against Burma as the British Empire sought to expand, but his dreams of glory ended abruptly when in 1825 he was shot in the most intimate part of the male anatomy.

During an understandably long convalescence, aided in true Empire fashion by daily cold baths, he began reading books about the Far East.

This later inspired him to lead the crew of a vast 142-ton sailing ship on a voyage to challenge Dutch control of southern Borneo.

His arrival in Sarawak in 1839 was timely. The region was controlled by the Sultan of neighbouring Brunei who was then facing a rag-tag uprising by local Malays.

He offered Brooke sovereignty over Sarawak if he could lead the Sultan’s army to victory against the rebels and the Englishman with a taste for lunatic danger quickly obliged.

As the newly-appointed Rajah, Brooke took charge of what amounted to 3,000 square miles of swamp, jungle and river, much of it populated by the Dayaks.

They marked important events in their lives by taking the heads of other people in the community. If a Dayak husband failed to present a human skull to his wife after the birth of a child then it was feared that the newborn would meet with illness or even death.

Likewise, no young Dayak warrior ever went courting without first donning an animal mask and skins and ambushing a fellow Dayak, often a woman or child from his own community.

He then made his intended a present of his victim’s skull.

Such acts were outlawed under the many new laws which James Brooke introduced to civilise Sarawak.

As self-appointed judge, he presided over court sessions in the front room of his own house, a hastily assembled plank-and-thatch affair in the capital Kuching.

With his pet orangutan, Betsy, scampering around in the background, the legal proceedings attracted much interest in Sarawak, although not for the reasons Brooke had intended.

For many, the main draw was the opportunity to place bets on the fate of those on trial including, in one most bizarre case, a man-eating crocodile.

This creature stood accused of killing a court translator who had toppled drunkenly into the river one night and, after much weighing of the arguments for and against its punishment, Brooke solemnly recorded the verdict in his journal.

‘I decided that he should be instantly killed without honours and he was dispatched accordingly; his head severed from his trunk and the body left exposed as a warning to all the other crocodiles that may inhabit these waters.’

Perhaps because of his delicate war injury, Brooke never married. Before his death in 1868, he nominated as heir his sister’s son Charles Johnson, a former sailor who changed his surname to Brooke upon becoming Rajah.

A beneficent and much-loved ruler who was 39 when he came to power, Charles extended the boundaries of the land under his control into the interior until it was the size of England, abolished slavery and built roads, waterworks and a even — in the style of a true Victorian — a railway.

He also encouraged his British officers to take native women as lovers in the hope that they would become ‘sleeping dictionaries’ who could teach them the local language. But at home he was somewhat less easy-going.

'Charles was something of a queer fish,’ his British wife, Margaret, once said. This was a somewhat understated description of a man who had lost his eye in a hunting accident and replaced it with a glass one, taken out of a stuffed albatross.

Charles forbade his sons to eat jam because he deemed it effeminate and his marriage became strained after he killed his wife’s pet doves and served them in a pie for her supper one night.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, she spent much of his 50-year period of rule back home in England. Seldom seen without a green parrot perched on her wrist, she lived in a house near Ascot called Greyfriars and became obsessed with finding wives for their three sons.

She did so by inviting eligible young women to join them in forming a musical ensemble known as the Greyfriars Orchestra. Among those attending the first rehearsal in 1902 was the Honourable Sylvia Brett — daughter of the 2nd Viscount Esher — later to become known by newspapers of the day as Sylvia, Queen of the Headhunters.

Although she had no musical skills, Sylvia’s contribution to the Greyfriars Orchestra was as a percussionist.

She obviously performed with beguiling effect, because one day the Brookes’ eldest son Vyner, then 28, made his move, asking if he might tune her drum.

A subsequent courtship resulted in their marriage in February 1911, after which they set sail for Sarawak.

By then, the Rajah’s Palace was an imposing affair, perched on a hill overlooking the river and comprising three airy bungalows with wide verandahs.

The couple would sleep through the afternoon, then have tea and play tennis or golf in the cool of the evening. It might have been an idyllic existence had Sylvia produced a son to ensure the succession after Charles and Vyner.

She became pregnant almost immediately, but the child she gave birth to in November 1911 was a girl — to Rajah Charles’s disappointment.

The following year, however, he received news from England that filled him with joy.

His second son Bertram had married Gladys Palmer, an heiress to the Huntley & Palmers biscuit fortune, and she’d had a boy called Anthony who would serve as an heir if Sylvia failed to produce a son of her own.

In jubilation, the Rajah ordered the firing of the 21-gun salute, which so alarmed the Dayak warriors.

Sylvia, who went on to have two more daughters but no sons, never forgave little Anthony for his much-heralded arrival in the world.

Sylvia would divide the rest of her life between battling to ensure that her daughters succeeded to the throne instead of Anthony and bestowing her sexual favours upon anyone she happened to find attractive.

She would divide the rest of her life between battling to ensure that her daughters succeeded to the throne instead of Anthony and bestowing her sexual favours upon anyone she happened to find attractive.

In this she was no worse than her husband, Vyner, who made no effort to conceal his liaisons with various Sarawakian mistresses. But in a European woman — and a Viscount’s daughter to boot — such behaviour was regarded as shocking. Not that this was likely to bother Sylvia.

By the time her father-in-law Rajah Charles Brooke died, in 1917, she was back in England, flaunting her exotic royal status. Sallying forth into London society in a Malay dress and yellow sarong, she topped her outfit off with a snakeskin headband and a tasselled red lacquer cane.

On her journey back to Sarawak to witness her husband Vyner’s oath of succession, she stopped in Cape Town for a few weeks. There she could not resist often disastrous dalliances with a series of South African men.

One came to her hotel room late at night and she discovered too late that, like her father-in-law, he had a glass eye.

‘He carefully took it out and placed it on the mantelpiece while I watched the performance quite speechless,’ she wrote in her memoirs. ‘Even had I been the most passionate woman in the world I could not have sinned before that baleful, glittering orb.’

She spent the night sleeping upright in a chair, while her intended paramour snored in her bed.

Perhaps her wantonness ran in her genes, because as her daughters reached an age where they were interested in men, she encouraged amorous escapades with young Government officers in Sarawak.

The antics of Princesses Gold, Pearl and Baba, as they were nicknamed by locals, fascinated the press in both Britain and America — and by the Thirties Sarawak had become something of a music-hall joke.

As he grew older, Vyner appeared to lose interest in the day-to-day business of government and considered abdicating. Since his brother Bertram had suffered a nervous breakdown and was incapable of rule, his natural successor was his nephew, Anthony.

In 1939, during one of Vyner’s annual pilgrimages to England for the flat-racing season, the 23-year-old heir apparent was left in charge of the country for six months.

He made a good impression on the British Colonial Office, despite his aunt Ranee Sylvia accusing him of inflated self-importance. She reported, among other things, that he had attached a gold cardboard crown to his car and ordered ox-carts and rickshaws to draw aside as he passed.

He denied these charges, but he was never allowed to inherit the rule of Sarawak because in 1946 Vyner agreed to cede it to the British Crown in return for a substantial financial settlement for him and his family. So it became Britain’s last colonial acquisition.

After failing in a long legal battle to have the sale of Sarawak reversed, Anthony began a second career as a self-styled ‘ambassador-at-large for the people of the world’, travelling the globe and campaigning for peace.

This put an increasing strain on his marriage to Kathleen Hudden, the sister of a Sarawak government official. They had three children but eventually separated, not least because of his increasingly bizarre beliefs.

At one point, he joined a New Age Commune in North-Eastern Scotland and adopted their belief that flying saucers would one day bring ‘peace on earth and to the brotherhood of man’.

He and Kathleen finally divorced in 1973 when he told her he was about to be contacted by extra-terrestrials and did not want her caught up in whatever dramas ensued.

He went on to marry a peace campaigner from Sweden who was 18 years his junior. Together they travelled the world, producing a newsletter which focused on issues, including environmental protection and the rights of indigenous people, before finally settling in New Zealand, 5,000 miles from the land he once dreamed of ruling.

We will never know how Sarawak would have fared if he had ruled for longer than those brief six months, but these details of his later life suggest one thing.

When it came to continuing his family’s tradition of idiosyncratic government, history would not have been disappointed in Anthony Brooke, the last of the White Rajahs.

Monday, July 06, 2015

Agreement of Malaysia

,

Exposing the Truth

,

Fact

,

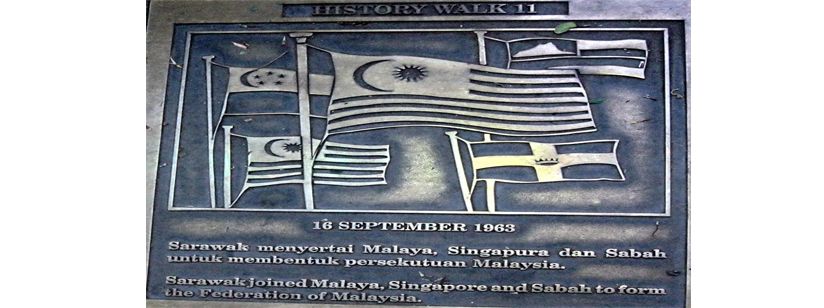

Federation of Malaysia 16 September 1963

,

History

,

Independence

,

Separation

,

Singapore

No comments

Singapore Separates From Malaysia And Becomes Independent on August 9th, 1965

On 9 August 1965, Singapore separated from Malaysia to become an independent and sovereign state.[1] The separation was the result of deep political and economic differences between the ruling parties of Singapore and Malaysia,[2] which created communal tensions that resulted in racial riots in July and September 1964.[3] At a press conference announcing the separation, then Singapore Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew was overcome by emotions and broke down. Singapore’s union with Malaysia had lasted for less than 23 months.[4]

Singapore in Malaysia

Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew signed the Malaysia Agreement in London on 9 July 1963.[5] The agreement spelt out the terms for the formation of the Federation of Malaysia, comprising Singapore, Malaya, Sarawak and North Borneo (Sabah), which was to take place on 31 August 1963.[6] The terms for Singapore’s entry into Malaysia, which were agreed upon by both the Singapore and federal governments, were published in a White Paper in November 1961.[7] This White Paper documented the outcome of talks between Lee and then Malayan Prime Minister Tunku Abdul Rahman on Singapore’s inclusion into Malaysia. The terms included the margins of Singapore's autonomy, Singapore's political representation in the federal government, the status of Singapore citizens and Singapore’s revenue contribution to the federal government.[8] Prior to the signing of the Malaysia Agreement in London, there was a week of “arduous and gruelling negotiations” over the more thorny issues of a common market between Singapore and Malaya, and the portion of Singapore’s revenue and taxes that would go to the federal government.[9] With these issues settled, Singapore began its journey as part of Malaysia.

A Difficult Union

Even before the proclamation of the formation of the Federation of Malaysia on 16 September 1963, Singapore and Malayan leaders were mindful that the differences in the political approach and economic conditions between the two countries “cannot be wiped out overnight”.[10] This, however, did not prevent sharp exchanges between the leaders of both countries throughout the period of the union. The slow progress of the creation of a common market and the difficulty in getting pioneer status from Kula Lumpur for Singapore industries frustrated Singapore leaders, while Kuala Lumpur was dissatisfied with Singapore's dogged response to the federal government’s clamour for increased revenue contribution to combat the Indonesian Confrontation, and for an agreed loan to develop Sabah and Sarawak.[11]

At the political front, the grossly imbalanced Malay-Chinese population in both countries made each vulnerable to communal prejudices which were played up by political leaders. The two major political parties in Malaysia, the People’s Action Party (PAP) and the United Malays National Organisation (UMNO), were soon accusing one another of communalism. The accusations escalated into tensions until they erupted into racial violence in Singapore on 21 July and 2 September 1964.[12] Despite agreeing to a two-year truce in September 1964, the acrimony between UMNO and PAP soon flared up again. At the heart of the rift was Lee’s multi-racial slogan, “Malaysian Malaysia”, which sowed deep distrust among UMNO leaders, especially the “ultras”, who viewed his vision of a non-communal Malaysia as a challenge to their party’s raison d'être of undisputed Malay dominance.[13]

Separation

By the second half of 1965, the stormy political climate in Malaysia showed no signs of easing. Tunku Abdul Rahman, who had become the Malaysian Prime Minister, was pressed to intervene to avoid a repeat of the communal clashes that had taken place in 1964. During his London trip to attend the Commonwealth Prime Ministers' Conference in June 1965, the Tunku decided that severing Singapore from the federation was the only course and communicated this to his deputy, Tun Abdul Razak, who was instructed to sound out the senior Malaysian ministers and lay the groundwork for separation.[14] By the time the Tunku returned to Kuala Lumpur on 5 August, Singapore’s days in the federation were numbered.[15]

The week leading to 9 August 1965 was a busy time for the leaders of both countries as by this time, separation had become a certainty.[16] Negotiations were, however, done in complete secrecy. In Singapore, not only were civil servants and permanent secretaries kept in the dark, but some senior PAP cabinet members, most notably Deputy Prime Minister Toh Chin Chye and Culture Minister Rajaratnam, were also clueless. Leading the negotiations for Singapore was then Finance Minister Goh Keng Swee, and for Malaysia, Tun Razak.[17] Razak was aiming to convene a federal parliament sitting on 9 August and was pushing for the legal paperwork for the release of Singapore to be tabled at that session.[18] In Singapore, Lee had asked then Law Minister E. W. Barker to draft the separation agreement at the end of July, along with other legal documents such as the Proclamation of Independence.[19]

As the deadline of 9 August neared, Goh and Barker made arrangements to travel to Kuala Lumpur to finalise the separation, arriving quietly in the capital on 6 August. Lee, who was in Cameron Highlands at that time, left for Kuala Lumpur and also arrived on 6 August to study and approve the separation documents. Thereafter, the separation draft prepared by Barker occupied the attention of five men – Razak, Malaysian Attorney-General Kadir Yusof, Malaysian Home Affairs Minister Ismail bin Dato Abdul Rahman, Barker and Goh. The final version, which included a few amendments and insertions, were typed late that night and signed by Goh, Barker, Razak, Ismail, Malaysian Finance Minister Tan Siew Sin and Malaysian Minister for Works V. T. Sambanthan well after midnight.[20]

After Lee was shown the final signed separation documents by Barker, he called Toh and Rajaratnam in Singapore to meet him the following morning. Arriving in Kuala Lumpur separately on 7 August, both Toh and Rajaratnam were particularly distraught when Lee told them of the news, and were not willing to sign the agreement.[21] However, a letter written by the Tunku to Toh stressing the former’s irrevocable decision – that there was “absolutely no other way out” – left them with no choice.[22] Realising that their persistence to pursue the status quo could well mean bloodshed, both Toh and Rajaratnam reluctantly signed.[23]

Lee then flew back to Singapore on 8 August on a Royal Malaysian Air Force (RMAF) jet so that he could get the separation agreement signed by the rest of his cabinet members. Two other individuals were called upon to assist with the task to meet the 9 August deadline: John Le Cain, the Police Commissioner, to ensure law and order, and Stanley Stewart, head of the Singapore Civil Service, to prepare and print the special gazette and proclamation of independence notices.[24] The Government Printing Office (GPO) had to recall its staff overnight, and to keep the lid on the separation, Stewart locked the GPO.[25] Encoded messages on the separation were also dispatched to the British, Australian and New Zealand prime ministers in the wee hours.[26]

Similarly in Kuala Lumpur on 8 August, things also moved swiftly as Razak had to ensure that everything was ready for the Tunku’s address to the federal parliament the following day, where he would move a bill to amend the constitution that would provide for Singapore’s departure from the Federation. Razak was also waiting for the fully signed separation agreement from Singapore to allay possible suggestions that Singapore was expelled from Malaysia. Only when the RMAF craft sent to Singapore to collect the document bearing the signatures of the entire Singapore cabinet arrived in Kuala Lumpur did he share the purpose of the 9 August parliament session with the chief ministers, mentri besars and state rulers in the Federation.[27]

The Birth of Singapore

The proclamation declaring Singapore’s independence was announced on Radio Singapore at 10:00 am on 9 August 1965.[28] Simultaneously in Kuala Lumpur, the Tunku announced the separation to the federal parliament. He then moved a resolution to enact the Constitution of Malaysia (Singapore Amendment) Bill, 1965, that would allow Singapore to leave Malaysia and become an independent and sovereign state. The bill was passed with a 126-0 vote and given the royal assent by the end of the day.[29] Singapore TV also aired the press conference called by Lee at 4:30 p.m.[30] During the press conference, Lee explained why the separation was inevitable despite his long-standing belief in the merger, and called on the people to remain firm and calm. Filled with emotions and his eyes brimming with tears, Lee had given Singaporeans a glimpse of their leader’s “moment of anguish”.[31]

Many rallied behind the news of the separation with relief although the manner of its announcement came as a shock and was initially greeted with disappointment and regret.[32] It was slightly less than two years ago that the people of Singapore had backed Lee’s merger through their votes in the September 1962 referendum.[33] However when merger came, the greater share of it was marked by constant differences and bitter political wrangling between leaders of the two nations.[34] Although all signs were pointing to trouble, very few were prepared for the dramatic end to Singapore’s union with Malaysia.

Anthony Brooke

Anthony Brooke, who died on March 2 aged 98, was heir to the throne of Sarawak and briefly ruled the romantic jungle kingdom on Borneo with the powers of the last White Rajah.

Brooke's English family had been the absolute rulers of Sarawak for three generations. Popularly known as the White Rajahs, they had their own money, stamps, flag and constabulary, and the power of life and death over their various subjects – Malays, Chinese and Dyak tribesmen, a few of whom still indulged in the grisly custom of headhunting.

The founder of the Brooke Raj was Anthony's great-great-uncle, James, who in 1839 sailed to the East with dreams of extending British influence throughout the Malay Archipelago. At Singapore, the Governor asked him to take a present to the ruler of Sarawak, then under the suzerainty of the Sultan of Brunei, to thank him for saving some shipwrecked British sailors.

When he got there, Brooke found Sarawak's Dyak tribesmen in revolt against an unfair system of taxation, and by 1841 the desperate ruler was prepared to give him the government and revenues of Sarawak if he could suppress the uprising, which he did.

On his return to London, Brooke was presented to Queen Victoria as Rajah of Sarawak, and knighted. In Sarawak, meanwhile, he won a devoted following with his integrity and frank exuberance. Each day he would stroll about the Malay kampungs, Chinese shophouses and Dyak longhouses, chatting to his subjects, and he was always open to visits at his bungalow. He introduced a just code of laws and enlisted the help of his friend Admiral Henry Keppel to clear up the piracy along Sarawak's coastline.

Among those serving in Keppel's ship, Dido, was James Brooke's nephew, Charles Johnson, who soon entered his bachelor uncle's service and eventually succeeded him as Rajah in 1868, whereupon he took the name of Brooke. A austere character – he deemed jam "effeminate" and replaced his lost eye with a glass one from a stuffed albatross – Rajah Charles nevertheless proved a notably effective and benevolent ruler. He extended Sarawak into the interior (it was eventually the size of England), abolished slavery, rebuilt the capital Kuching and constructed roads, waterworks and even a short railway.

Charles's first three legitimate children all died within a week from cholera while sailing up the Red Sea on their way back to England on leave, but his wife subsequently bore him three more sons, the eldest of whom, Charles Vyner Brooke, known as Vyner, was destined to become the third Rajah of Sarawak. The couple's second son, Bertram, was Anthony's father.

Anthony Walter Dayrell Brooke, always known in his family as Peter, was born on December 10 1912, the fourth child and only son of Bertram and his wife Gladys, the only daughter of Sir Walter Palmer, first and last Baronet – and thus heiress to a sizeable slice of the Huntley & Palmer biscuit fortune.

Anthony's mother was a restless exhibitionist who went through a number of religious conversions. In 1932 she converted to Islam while on a flight from Croydon to Paris, after which she went by the name of Khair-ul-Nissa (Fairest of Women).

She separated from her more retiring husband when Anthony was four but, having produced the longed-for son, remained in favour with her father-in-law, who ordered a 21-gun salute at Kuching when Anthony was born. The old Rajah was far less well disposed towards Vyner's equally flamboyant wife, Sylvia, who managed only daughters.

In the Rajah's political will he bequeathed sovereignty to Vyner but made no secret of his preference for Bertram, who would have to be consulted on any "material developments", and stand in for his brother whenever Vyner was away from the country. After Charles's death in 191, Vyner and Bertram effectively shared power, each spending half the year acting as Rajah in Sarawak.

As for Anthony, he grew up in England, where he was educated at Eton. After a year at Trinity, Cambridge, he studied Malay language and Muslim law at the School of Oriental Studies in London, before travelling for the first time to Borneo in June 1934.

Anthony was seconded to the Malayan Civil Service, serving as an acting resident and magistrate, before returning to Sarawak in 1936. After spells at the outstations of Nanga Meluan and Marudi, and at the Kuching Secretariat, he returned to England in 1938 to study colonial administration at Oxford and complete his grooming as his uncle's heir.

The following year Anthony returned to Sarawak to become district officer at Mukah. Bertram, meanwhile, had become incapable, after a nervous breakdown, of discharging his responsibilities in the power-sharing arrangement with Vyner, and so in April 1939 Vyner appointed Anthony as Rajah Muda (Heir Apparent) and Officer Administering the Government during his annual periods of leave in England.

During his six months in charge of Sarawak, Anthony enacted various education reforms and amended the penal code on whipping, the protection of women and girls and the punishment of mutiny; he also issued a proclamation supporting Britain's declaration of war against Germany and Italy.

Overall he made a favourable impression on the Governor of Straits Settlements, Sir Shenton Thomas, who noted that he seemed enthusiastic to make Sarawak a model state. The Colonial Office, too, felt that here was a man with whom it could do business, unlike the increasingly eccentric Rajah Vyner.

When Vyner returned to Sarawak in 1939 on outbreak of war in Europe, however, he was told by senior members of the Sarawak Service that his nephew had been supercilious, reluctant to take advice and had displayed a tendency to judge officers according to their horoscopes. Anthony had by then left Sarawak to get married and it was on his way back from honeymoon in Sumatra that he heard his uncle had deprived him of the title of Rajah Muda, saying he was "not yet fitted to exercise the responsibilities of this high position".

Ranee Sylvia inferred that part of the problem had been Anthony's marriage to Kathleen Hudden, the "commoner" sister of a Sarawak government official. "I don't like to be snobbish," she told reporters, "but the natives are very particular about these things." The unreliable Ranee later alleged that Anthony had been guilty of folie de grandeur, having cardboard crowns pinned to his car and ordering traffic to draw aside as he approached. Anthony denied this.

The furore eventually subsided, a peace was brokered, and Anthony returned to Sarawak as a district officer in early 1941, and was due to be reinstated as Rajah Muda. However, in September he was again expelled from the country by Vyner, this time for objecting to various aspects of a proposed new constitution. Three months later, in December 1941, Sarawak fell to the Japanese.

By this time, Anthony was back in England, enrolled as a private soldier in the British Army. In 1944, by which time he was on Lord Louis Mountbatten's staff in Ceylon, the British government approached Rajah Vyner suggesting they discuss how Sarawak and Britain might be "marched together in the future".

Reluctant to involve himself in such discussions, Vyner once again turned to his nephew, restoring him again as Rajah Muda, and appointing him head of a Provisional Government of Sarawak in London to explore what the British government had in mind. The talks quickly broke down when it emerged that Britain intended that Sarawak join the Empire, an outcome to which Anthony was vehemently opposed.

Not to be frustrated, the British government made a direct approach after the war ended to the Rajah, and he agreed to cede Sarawak to the British Crown in return for a financial settlement for him and his family. He then wrote to Anthony once again abolishing his title of Rajah Muda.

The cession was put to a vote of the State Council in Kuching, where the majority of the indigenous members voted against it, but it was carried by white government officials loyal to the Rajah. Hence, on July 1 1946, Sarawak became Britain's last colonial acquisition.

There followed a five-year campaign in Sarawak aimed at revoking its new colonial status, which Anthony Brooke helped direct from his house in Singapore. He urged that it be non-violent, but in 1949, after the second Governor, Duncan Stewart, was assassinated by a young Malay, he came under the scrutiny of MI5, who wanted to "get wind of any other plots he and his associates might be hatching". But they turned up no evidence that he had known of the assassination plot.

For his own part, Anthony Brooke was quick to distance himself from the extremists, and when his legal challenge to the cession was finally dismissed by the Privy Council in 1951, he renounced once and for all his claim to the throne of Sarawak and sent a cable to Kuching appealing to the anti-cessionists to cease their agitation and accept His Majesty's Government.

The anti-cessionists instead continued their resistance to colonial rule until 1963, when Sarawak was included in the newly independent federation of Malaysia. Two years later, Anthony Brooke was welcomed back by the new Sarawak Government for a nostalgic visit.

By this time he had embarked on a second career as a self-styled "travelling salesman" for world peace. In the late 1950s, he led a campaign to put morality back into British politics, and in the 1960s he toured the world on a "peace pilgrimage", meeting Nehru, Zhou En-lai and U Nu of Burma, and walking across the Punjab with the Indian saint Vinoba Bhave. He lived with the New Age commune at Findhorn, in the northeast of Scotland, adopting their belief that flying saucers would bring "peace on earth and the brotherhood of man".

After divorcing his first wife in 1973, he married Gita Keiller, from Sweden, 18 years his junior, and together they founded Operation Peace Through Unity, which produced a quarterly newsletter, Many to Many, with "news items, strategies, poems and letters from around the world, for use in the cause of peace, environmental protection and the rights of indigenous peoples".

They continued their globe-trotting campaign until the late 1980s, when they came to roost in a wooden villa on a hill above the town of Wanganui on the north island of New Zealand. Towards the end of his life, Anthony Brooke remained saint-like in his good nature, and remarkably forgiving about those members of his family who had conspired to deprive him of his singular inheritance.

He is survived by his second wife and by a son and a daughter from his previous marriage; another daughter predeceased him.